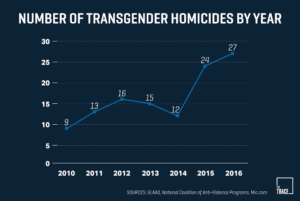

Transgender people face disproportionately high rates of violence. According to the Human Rights Campaign, twenty-three transgender people were murdered in the United States in 2016, and as of November 2017, twenty-eight transgender people were murdered in the year. Despite the widespread aggression targeted at transgender people, especially trans women of color, the culprits are rarely brought to justice. Even when cases are brought to trial, justice is not always served, as shown by several high-profile court cases. There are two main reasons why violence against transgender people is common and the perpetrators are not condemned. The trope of the deceiving transgender woman who tricks heterosexual men is one, and toxic masculinity that condones violence against anyone perceived as a threat to said masculinity is another. These two issues are deeply connected, and in this piece, I wish to uncover how, together, they have been used to criminalize existence as a transgender person and pardon murderers.

Transgender people face disproportionately high rates of violence. According to the Human Rights Campaign, twenty-three transgender people were murdered in the United States in 2016, and as of November 2017, twenty-eight transgender people were murdered in the year. Despite the widespread aggression targeted at transgender people, especially trans women of color, the culprits are rarely brought to justice. Even when cases are brought to trial, justice is not always served, as shown by several high-profile court cases. There are two main reasons why violence against transgender people is common and the perpetrators are not condemned. The trope of the deceiving transgender woman who tricks heterosexual men is one, and toxic masculinity that condones violence against anyone perceived as a threat to said masculinity is another. These two issues are deeply connected, and in this piece, I wish to uncover how, together, they have been used to criminalize existence as a transgender person and pardon murderers.

To avoid murder charges in anti-trans violence cases, the defendant will claim the “trans panic defense.” The trans panic defense, defined by the LGBT Bar, an organization that works for justice for LGBT individuals in the legal system, is the claim that “the victim’s sexual orientation or gender identity not only explain[s] – but excuse[s] – their loss of self-control and subsequent assault of an LGBT individual.” The trans panic defense attempts to absolve the offender of responsibility for their actions because they were so disturbed by the victim’s gender identity that their violence was involuntary. This seems fictitious, but there are many examples of court cases in which this defense was asserted. The “panic defense” is rooted in a real legal defense, the “defense of provocation”. According to the Legal Dictionary, provocation is “conduct by which one induces another to do a particular deed; the act of inducing rage, anger, or resentment in another person that may cause that person to engage in an illegal act.” The defense of provocation is used to lessen a sentence, usually from murder to manslaughter – it is only a partial defense. It is not used exclusively in cases of “trans panic”, but also “gay panic”, when a heterosexual man is offended by a gay man’s advance, and in cases in which a husband murders his wife, for infidelity or other reasons. The 1975 U.S. Supreme Court case Mullaney v. Wilbur, in which the defendant was charged with murdering a gay man who made an advance on him, determined that if the defendant claimed that they were moved to a heat of passion in committing the murder, the prosecution was required to prove that that was untrue. This case set a precedent for not requiring the defendant to prove that he was provoked into a heat of passion, thus making it easier for defendants to claim the panic defense.

An Unjust Precedent

In 2008, in Oxnard, California, middle school student Brandon McInerney shot and killed his classmate, Larry King. King was gay (some believe he was actually transgender – he asked teachers to call him Leticia, and had written it on his papers), wore heels and makeup, and had reportedly made passes at McInerney. The defense argued that McInerney was the “product of a violent and dysfunctional home and had reached an emotional breaking point” (L.A. Times) because of King’s flirting. A mistrial was declared at first when the jury was torn between manslaughter and murder – the panic defense used by McInerney’s lawyers convinced several jurors that the killing had taken place in the heat of passion, despite McInerney informing another student of his intention to bring a gun to school, sitting behind King, and staring at him for a long time before shooting him. Eventually, McInerney pleaded guilty to second-degree murder, manslaughter, and the use of a firearm, and was sentenced to 21 years in prison, despite prosecutors seeking first-degree murder and hate crime charges. This case showed that although there was considerable evidence of premeditation and homophobia, the jury was swayed by the panic defense. Out of twelve jurors, seven believed that the gay panic defense was reason enough to not convict him of murder (Lee & Kwan 104). The jury had been instructed to not let any bias affect their decisions, but one juror wrote to the D.A.’s office after the trial, saying that “King brought on his own death by engaging in ‘deviant behavior’” (Lee & Kwan 105). They believed that King’s actions and identity were good enough reasons to provoke his violent actions.

Gwen Araujo, SF Weekly

In 2002, in Newark, California, transgender woman Gwen Araujo was beaten to death by four men. She had sexual relations with two of them, and when they discovered that she was biologically male by cornering her and exposing her, they grew angry and killed her[i]. In the trial, defense lawyers claimed that the discovery of Araujo’s biological sex had sent the men into a “heat of passion” and that they were only guilty of manslaughter[ii]. They also claimed that the men had been violated by Araujo’s concealing of her “true” male identity, and that she had betrayed them by withholding it, thereby provoking a “primal” instinct that caused them to kill her[iii]. The prosecutor reported that the jury did not accept the panic defense, while the defense insisted they did, so it is impossible to know if the defense deeply influenced their decision. However, the jury was hung between first-degree and second-degree murder, resulting in a mistrial[iii]. In the second trial, two of the men were convicted of second-degree murder, and a third pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter[iii]. None of the men were convicted of a hate crime[iii]. While the offenders were eventually convicted of murder, the fact that the conviction required two trials, angered many people, who called for the law to be changed[iv]. The Gwen Araujo Justice for Victims Act, signed into law in California in 2006, instructed jurors not to let bias affect their decisions, banned decisions by biased juries, and prohibited the panic defense in any situation[iv]. The law was updated in 2014 to specifically bar the claim that the discovery of the victim’s gender identity or sexual orientation provoked violence[v]. The trans panic defense has also been banned in Illinois, and a bill is making its way through Rhode Island’s legislature. This means it is still legal to use the trans panic defense in 48 states. Why is this defense still considered to be acceptable in society?

Toxic masculinity (n.): a specific model of manhood, geared towards dominance and control. It’s a manhood that views women and LGBT people as inferior, sees sex as an act not of affection but domination, and which valorizes violence as the way to prove one’s self to the world (Amanda Marcotte, Salon).

The defense of provocation, which claims that a reasonable person would be provoked to violence by the actions of the victim, being used in the case of trans panic means that a reasonable man would be provoked to violence upon discovering his sexual partner is a transgender woman, and therefore a man in his mind. The trans panic defense is deeply rooted in assumptions about masculinity, or in this case, toxic masculinity. The toxic masculinity that excuses and enables violence depends on two factors: “not being a woman and not being gay”[vi]. Following the rules of toxic masculinity, a heterosexual man who discovers that his woman sexual partner is male must defend his masculinity. The violent reaction is a way for the man to prove that he is not gay and not a woman. The act of murder shows that he is repulsed by the idea of having sex with men and is therefore not gay[vii]. The violence shows that he is not feminine, as this type of masculinity is associated with aggression and strength[vii].

In a trial, jurors may relate to the man’s predicament. If violence is considered a central part of masculinity, a man is supposedly not at fault for reacting violently – toxic masculinity absolves him of responsibility for his actions. A male juror may be repulsed at the thought of finding himself in a similar situation, and sympathize with the defendant, and a female juror could feel the same way[v]. Additionally, transgender women have historically been treated as deceivers, men disguised as women who lure heterosexual men into intercourse as a way of tricking them into homosexuality. From this point of view, genitalia are the essence of gender, so transgender women are pretending[viii]. This belief leads to situations like Gwen Araujo’s, in which the men cornered her, exposed her, and decided she was actually a “man.” Transgender bodies are treated as subjects in the medical community, and transgender people often have a hard time accessing gender-confirming surgeries because doctors doubt that they are really transgender, prioritizing their own personal opinion over the gender identity of the patient[ix]. The societal view that transgender people are deceiving legitimizes the trans panic defense. If transgender women are deceptive and lying about their identity, then their “discovery” constitutes panic. The “deception” causes a reaction in a man affected by toxic masculinity, and the broader belief that transgender people are deceivers excuses the reaction, both in public and in court.

As long as toxic masculinity is accepted as a part of society, innocent transgender women will continue to be victimized and blamed for their own murders. As more states adopt anti-trans panic defense laws, one can hope that this defense will be used less. However, while these laws may bring justice to the victims, they cannot prevent the killings. Our society must examine the root causes of anti-trans violence and reinforce the necessity of respecting trans identities if we want the murders of transgender women to end.

[i] Bettcher, Talia Mae. “Evil Deceivers and Make-Believers: On Transphobic Violence and the Politics of Illusion.” Hypatia, vol. 22, no. 3, 2007, pp. 43. JSTOR.

[ii] Bettcher 44

[iii] Bettcher 45

[iv] Lee, Cynthia and Kwan, Peter Kar Yu, “The Trans Panic Defense: Heteronormativity, and the Murder of Transgender Women.” 66 Hastings L.J. 77 (2014), pp. 107. GWU Law School Public Law Research Paper No. 2014-10.

[v] Lee & Kwan 108

[vi] Lee & Kwan 109

[vii] Lee & Kwan 110

[viii] Bettcher 48

[ix] Meyerowitz, Joanne J. How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality in the United States. Harvard Univ. Press, 2009, pp. 130-167.

This post is great. Prior to joining this class, I had never heard of the panic defense. I was absolutely floored when I learned in class that this is a real defense that is systematically used to justify extreme violence towards trans and gay people. This post does a great job of helping the reader understand how this type of defense is used without “rubbing their nose in it”. Your use of specific cases to bolster your argument was very effective and helped me fully understand your argument as a reader. I also really enjoyed the way that you incorporated the concept of toxic masculinity (and even defined it for readers who are unfamiliar with it)! Additionally, your introduction and conclusion are both artfully succinct. With your introduction, I felt comfortably situated in the context of your argument. Your conclusion not only summarized your argument effectively, but the “call to action” you included at the end of it also was very powerful. Overall, this is an awesome post and I greatly appreciate the research, passion, and effort put into it.

Thank you so much for this post. I was unaware that 48 states still allow the “panic” excuse for murder; it is sadly unsurprisingly but disgustingly trans antagonistic. It is just another example of the systemic oppression of trans individuals in our legal system. The judicial system itself in America is deeply troubling and undeniably broken, yet it prevails because it upholds an oppressive status quo that marginalizes certain populations and continuously benefits the privileged.

It is disturbing that “trans panic” defenses work in court, especially considering they normalize masculine violence and trans and homo antagonism in a very dangerous way. I am curious as to how a case would go if a woman murdered / assaulted a trans man; would a “panic” defense work in the same way, or would assumptions about normative female passivity and non-violence render such a defense illegitimate? As we have learned in class, courts have historically failed trans individuals and inhumanly criminalized them (think of cross-dressing laws, for example). Many trans people end up in jail themselves after assault, and more still are faced with oppression, misgendering, and continued assault in prisons and by the police. This led me to think about how the judicial system as a whole and its productivity in terms of trans activism. Can political change in the courts actually change the lives of trans individuals? I think it is obvious that the “panic” defenses are gross and inexcusable, and it is necessary that they are discredited in all states. My concern is that another similar type of defense would pop up in order to ensure trans antagonism prevails and that cisgender attackers get lighter sentences because of their “confusion.” I am curious as to how trans antagonism can be dealt within the entire judicial system itself.