I am a child of immigrants. Being raised by immigrants means being raised with the same norms and expectations that one would expect from traditional culture – for me that is Indian, but specifically Punjabi, norms. Deviance was not allowed; the thought was not even allowed to enter my mind. I grew up on stories that just reinforced why I was not supposed to act a certain way, talk a certain way, be a certain way because “I’m a girl,” “I’m Punjabi,” or “I’m Sikh,” and the community would reinforce norms by pairing them with the ever-present concern of danger.

The stories that have had a lasting impact on me are those that involve violence. My mom once told me about the son of her friend at work (but this is one of many – there are many “sons” and “daughters” that have been made examples of within the community). They are a Muslim family, and her son came out as gay. Because of his coming out, he was beaten up severely by his community, so the family moved him to somewhere else. This story was not meant for me to feel pity for him, but to emphasize the importance of making sure I stick to the cisgender heteronormative patriarchal structure within society. His being beaten was a warning; if I was to come out as a lesbian, I was likely to face a similar fate. In fact, I should not be anything that a ‘typical’ Indian daughter would not be, otherwise the repercussions from my friends, family, and community would literally be devastating and life threatening. While his family moved him away for his safety, his removal from the community can also be understood as a way to solve the “problem” of his sexuality.

Sending the “problem” away seems to be an easy way to enforce the norms. A group that has been cast aside in India is the hijra. Hijra are officially recognized as a third gender in South Asia, and they are people who do not fall into the conventional definitions of male or female. A video on the hijra community within India that Refinery29 did a few years ago still resonates with me. As one of the hijra women said, “The minute the family realized that this person is not a regular gender, he probably beg[s] that human being [to] please leave because it’s [bringing] shame on the family.” Some of the hijra women in the video said they were ostracized because society would rather them be a boy than a girl. The hijra community has received some media recognition in America, but many transgender issues in Asian communities are still invisible. To learn more, I reached out to an online Asian community which has members from all over the world. It is important to have actual trans Asian voices heard, so I asked if anyone would be willing to share their experiences with me. Fortunately, I had three people reach out to me in personal messages. I believe that sharing their stories can help to render trans Asians visible, humanizing their experiences to show that trans identities are not “problems” to be “fixed.”

The first person I talked with was Lia who uses “she”/“they” pronouns. Lia is a Chinese Filipinx high school student who is currently residing in California with her father (who was raised in America for most of his life), while her mother resides in China (and is “very strictly Chinese”). Lia identifies as trans. The second person I talked with was [Anonymous] who uses “they” pronouns. [Anonymous] is a Hong Konger musician who is currently residing in Hong Kong (although they spent five years in Minnesota). They also identify as trans. The third, and final, person I talked with was AJ who uses “they” pronouns. AJ is a Taiwanese American artist/activist who is currently residing in America. They identify as trans, but also use the following terms to describe their identity: genderqueer, gender non-conforming, greygender, and genderfluid. Although each individual is unique, I have seen some patterns emerge from their personal stories.

The first pattern that I identified was the lack of knowledge on trans identities in the Asian communities the participants are living in. This unawareness reminded me of Z Nicolazzo’s Trans* in College. The book explores the lives of multiple trans students at a particular American college, and analyzes the common themes of these students’ campus experience. One participant in Nicolazzo’s study, Micah, said that people “don’t really know what it [transgressive gender expression] is, so they don’t ask” (78). Trans identities were rendered invisible and put aside because it was easier to do so in a world where it is unknown. The attitude in many Asian communities in regards to trans identity is similar; the lack of mainstream representation of trans people in these communities perpetuates cisgender norms. We can see that the lack of awareness of trans identity in the public, and specifically in Asian communities, might lead to trans individuals coming into their identity later on in their life because of the lack of terminology and words to express themselves.

Lia said that, “We have so many Asian kids at my school – they all are East Asian, most are cis/straight, most don’t have detailed knowledge of gender identities and sexual orientation even though we live in California.” AJ said that their art helps them come to terms with themself because it was hard to do so, especially as a first generation person and because the Chinese do not “really have a non-derogatory and non-academic word for being trans.” [Anonymous] said that they did not “come into the realization that [they were] trans until later in [their] life (post college),” and it was largely due to the fact that [Anonymous] “did not have access to those vocab and dialogue when [they were] growing up. Let alone knowing other trans people.” The power of knowledge is so important because it can help people understand their own identity. [Anonymous] continues by saying that “knowing other trans people [definitely] helped [them] come to terms with [their] gender.

A struggle that [Anonymous] faces is of people equating their gender identity to their sexuality. [Anonymous] was interviewed by Amnesty International earlier this month stating that it is “harder for [them] to love, especially in Hong Kong where the relationships… are very cisgender… and heteronormative….” [Anonymous] is currently in a relationship, but when the two go out “people look at [them] as either a gay or lesbian couple.” This made me think of Nicolazzo’s concept of “compulsory heterogenderism.” Compulsory heterogenderism is the conflation of one’s gender and its misconstrual of sexuality. Nicolazzo writes that trans individuals put aside their identities in order to aid “nontrans* individuals [in making] sense of the participants’ gender… through their sexuality.” [Anonymous]’s gender performance is often understood by cis people to determine their sexuality based on the heterosexual gaze, but [Anonymous] refuses to make their identity invisible to others.

Another pattern I saw was the role of family in trans Asian lives. As I mentioned above, any sign of deviance is not tolerated in Asian communities– which includes sexuality and gender. The communities’ intolerance is especially concerning given the amount of literature on the affirmative model having positive outcomes. In other words, trans children that are supported by their families often experience happier childhoods. Studies have shown that family-supported transgender children will have levels of depression similar to those of cisgender children. On the other hand, transgender children who are not supported by their families will show higher levels of depression, which is why multiple studies have lauded the use of affirmative models. Sadly, transgender people who do not have an affirming experience and instead face a lack of support and family rejection are more likely to have attempted suicide. Unfortunately, trans adolescents and young adults are more likely to be at risk of suicide. A study on Thai trans youth by Yadegarfard et al. published in Culture, Health & Sexuality compared 20-25 year-olds with 15-19 year-olds, with the younger participants reporting higher at-risk behavior. The younger participants would be those who are usually forced to stay at home with their families for financial and legal obligations. If their families were not supportive, then they would be living in an unsafe environment.

Unfortunately, this is resonating with the people I talked to. Lia, who is still in high school and thus under her parents’ rules, told me that she has “never felt safe or comfortable coming out as nonbinary to [her] parents.” In fact, when Lia told their mom that she had a girlfriend once, her mom “threatened to send [her] to a conversion camp in China.” Although their dad was described as “pretty liberal,” Lia said that he “still doesn’t understand my gender identity. He, like the rest of my Filipino relatives, encourages me to act, dress, and speak in a more feminine, stereotypical way. So, as far as being trans and Asian, I’ve always felt [that] just based off my parents and relatives, I could not be nonbinary and I could not be genuine to my gender identity AND be Chinese and FIlipinx.” [Anonymous] also has difficult conversations with their parents about their identities. [Anonymous] said that they “got blamed for not telling them anything” even though “it’s never been a safe environment for [them] to bring up anything. [They] didn’t want to tell them they could have an openly trans kid, or they can bury a dead kid with a closet as their coffin.” The most recent conversation with their parents was sparked by [Anonymous]’s latest radio interview. [Anonymous] went on to say that, “Maybe I don’t know what I’m bringing upon myself by going public, but discourses are necessary when it comes to social justice and equality. They ask if I have to be the one doing it. I still believe visibility is important. If there’s one non-binary person who listened to my radio interview and reconsidered their [suicide] attempt, I’ve done my job.” Although [Anonymous] has arguments with their parents about their identity and openness, [Anonymous] believes that it is for a better good by having visibility of a community that is too often made invisible. However, we can still see that not all trans Asian people have the option to be visible when their safety is at risk.

The lack of visibility in trans identities in Asian communities is perpetuated by the lack of trans Asian role models. In US News, Matt Kane, the then Associate Director of Entertainment Media at GLAAD, said, “What we’ve noticed is that in many ways transgender representation is still 20 years behind where the LGB representation is today.” GLAAD actually examined television archives over a ten-year period and found that “transgender characters were cast in a ‘victim’ role at least 40% of the time; transgender characters were cast as killers or villains in at least 21% of the catalogued episodes and storylines; the most common profession transgender characters were depicted as having was that of sex workers…; [and] anti-transgender slurs, language, and dialogue was present in at least 61% of the catalogued episodes and storylines.” This is just trans people in media – not even narrowing in on different aspects of their identity, such as their race and/or ethnicity. NPR talks about a newly released study that suggests that diversity in TV and film is so terrible that “the hashtag #OscarsSoWhite should probably be changed to #HollywoodSoWhite.” The study looked at different aspects of inclusion: gender, race, sexuality. The study found that “half the films and TV shows they analyzed had no Asian speaking characters…. Just 2 percent of speaking characters were identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transsexual, and more than half the LGBT characters in all the films they examined came from two movies.” I like watching a lot of Asian dramas (Indian, Korean, Vietnamese, Chinese, Taiwanese), but the only time I can remember a transgender character (not including the hijra) was in a recent Korean TV series, Black. However, the character did not even have a chance to function as a living character, let alone speaking, since they were the murder victim – simply a plot twist for the audience. There is a deficit of transgender characters period, but even more so when combined with an Asian background.

Lia told me that all of her “nonbinary role models are skinny, modelesque, androgynous white people.” Even though these nonbinary white people are their role models, Lia also says that she “looked too Asian femme to ever fit in with the white nonbinary role models the internet offered.” Since trans Asian celebrities (like Himitsu no Otome, Choi Han Bit, and Lady) are not mainstream or well-known, her role models “tend to be young people like me who are groundbreaking in some way and are forging new paths of representation for people of color, queer people of color, etc.” Lia also mentioned Amandla Stenberg as a particular role model for herself because Stenberg is “an incredible teen of color who uses the they/them identity [and is] committed and empowered and [an] activist, while being only nonbinary and not conforming to typical white nonbinary standards, and that is very inspiring.” AJ said, “In terms of representation, I find it interesting that it’s really hard to find people like me both in media and in real life, so most of my role models, or people I feel get closest to representing myself as a whole, tend to be (while still people of color), more specifically black or Latino POC, and that really comes down to a lot of LGBT+ identified Asians not really feeling safe or comfortable in coming out.” AJ also lists that their role models are Asians who are queer, but not trans. However, AJ talks about a recent role model, which is the Chinese-Pop music group called FFC–Acrush that is representing more androgynously, but their contracts with their management company do not allow them to disclose their sexuality or gender to the public, which AJ says “has been kind of frustrating.” [Anonymous] breaks from this mold since their role models were their Asian American friend, Siufung Law (a bodybuilder and lecturer on Gender Studies), Jes Tom (a stand-up comic), and AC Dumlao (an artist, activist, and Name Change Project Coordinator at the Transgender Legal Defense & Education Fund). [Anonymous] also feels that author Sam Dylan Finch’s “experiences about being trans and discovering that late in his life” resonates with them.

Representation is important, and just being visible is a form of activism. Lia said that it makes her “feel better that just by existing [she’s] changing their [nontrans] perspective on the world and on people and making them a little kinder and more tolerant.” Lia spends a lot of time writing, and they said that they “intentionally include trans people of color in [their] writing and share stories that center around trans people of color.” [Anonymous] told me that they “don’t want to make other people think [their] activism is self-serving/just to promote [their] music,” which does not negate the fact that their music is still empowering. In the aforementioned interview with Amnesty International, [Anonymous] said that they “try the best [they] can to talk about gender issues, if not specifically trans issues, when [they] are promoting [their] music.” AJ identifies themself as an artist and activist, and has been trying to create a coalition with their friends that acknowledges that LGBT+ issues are intersectional ones. A lot of their art focuses “a little more on [their] mental health and gay/trans identities and how hard it was to come to terms with those parts of themselves.”

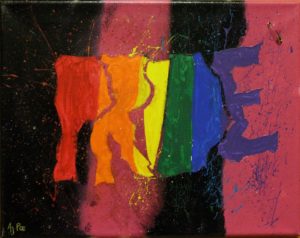

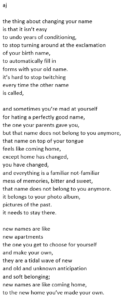

AJ said that their canvas piece, “Pride” (pictured), references how they “tried to hide [their] sexuality and trans-ness (more so [their] trans-ness than sexuality though) and how that doesn’t really work, kind of how it will all spill out anyway, and is an expression of [their] journey to come out to [them]self/learn to express [their] queerness (both in sexuality and gender) with pride. It’s kind of something that [they]’ve created in [their] journey to get over [their] internalized biphobia and transphobia.” Since the lettering style is inspired by graffiti, AJ wanted to express a sense of rebellion and resistance, which is a narrative that resonates with the LGBT+ community. They have also created a poem about their name, moving from their dead name to their chosen name:

The activism and artivism that the three trans Asians that I have talked to combines their raced bodies with their work. I believe that by existing as an individual who is both trans and Asian inherently creates discourse and visibility. Even though their work might not always talk about being trans or being Asian, by having the creator be both, it still emphasizes both identities by having a presence. Although the three have talked about not having trans Asian role models, I believe that the work they do can inspire others who identify the same way.

Although I obviously am unable to touch upon every nuance, I am so grateful to have learned more about the trans Asian communities from these three individuals, and I would like to express my thanks for them being so kind to explain and share their stories with me.

***Note: These quotes have been edited for spelling and clarity, but otherwise have been kept intact.

***Edited 3/15/18: Redacted the name and associated hyperlinks of one of my interviewees after a request to be anonymous.

Hi Baldeep,

I had the pleasure of reading yours before you posted, and I really like the changes you have made since I read it the first time.

Your post reminded me of the importance of online communities for people to find each other and share experiences. These spaces, I believe, are extra important for individuals who are marginalized and might have difficulty finding others that identify similarly or will otherwise understand their situation. The group that you met these folkx in is a great example of the power an online community has to connect trans individuals and to share stories.

I think your post does a really great job in thinking about all of the complexities when it comes identifying as a trans person of color. I am not trans nor a person of color, so I understand that I cannot fully comprehend your interviewees’ situations. But I believe you did a great job of sharing their stories while keeping in mind the difficulties trans people of color face because of their gender identities and their race. A blog post like this one on Asian identities is especially important; as you and I have discussed before, often discussions on race turn out to be quite literally black and white.

It seems to me like visibility in this community is also important because, like you say here, Asian trans identities are almost always ignored. I think this really came through when you talked about how Lia had trouble finding trans role models who were similar to her, leaving her feeling disconnected. It is important, though, that Asian trans individuals can connect with other trans role models who are people of color, even if they are not also Asian. I think your post did a great job of exploring these folx’ identities and highlighting both their struggles and their excellence.