Mainstream hip hop has recently become (at least more openly) a musical artform which can highlight the power, joy, and/or problems of queer life and existence. Popular hip hop and R&B artists like Frank Ocean, Azealia Banks, and Zebra Katz openly identify as queer, and the number of “out” artists in the genre is growing. One artist who has emerged on the transgressive hip hop scene is Mykki Blanco, a genderqueer rapper and performer who continuously shakes up gendered norms in the genre. Mykki’s work is difficult to locate within a strict definition of “queer rap,” but it is clear that she is one of many hip hop artists who are currently challenging the way hip hop portrays sexuality and gender.

While reading articles about Mykki shortly after discovering her music, I continuously found inconsistencies in the pronouns used for her. Some authors used only “she/her” pronouns, some only “he/his,” some interchangeably depending on if it referred to the artistic persona (Mykki) or the artist himself, Michael David Quattlebaum Jr. I’d argue that labeling Mykki Blanco as “her” and Michael David Quattlebaum Jr. as “him” perhaps oversimplifies the fluidity of her gender identity and performance. But most important is what Mykki herself says: “You can say ‘she’ and you can say ‘he,’ it’s literally fine to say either. One of the reasons that I’ve always been so elusive about my pronoun is that I’ve never thought that it mattered.”

So, in this blog post I will be referring to her with both she/her and he/his pronouns, because I think the disruption of static pronouns parallels Mykki’s purpose to “fuck with people.” He once said in an interview: “I remember telling my publicist, let’s fuck with people. Let’s send them pictures of me as a boy and still make them say ‘She.’” I think it’s important to note here that Mykki strongly defends any person’s right to choose their pronouns, static or not. According to Dazed Magazine, she “understand[s] that [cisgender] people can have trouble with it [fluid pronoun usage], but who cares?” She also stressed the point that cisgender people should take it upon themselves to learn about genderqueer pronoun usage. “Our whole entire world is run for the most part by a patriarchal heterosexual agenda, and I’m sorry, but if it [fluid pronoun usage] is too confusing for you now, watch this program, read a book, read a magazine.” She also posted on Instagram shortly after (later removed): “DON’T MISGENDER. IT’S AS EASY AS …. TRYING & LEARNING.”

Mykki described herself as an artsy femme on Twitter, so I have decided to explain her art this way instead of calling her a queer rapper (a label she does not identify with). Mykki’s talents extend beyond her rap; she is a performance artist, poet, and intersectional activist. Her music style varies from album to album, from “unlistenable noise shit” to “feminist punk hip-hop.” His gender identity, artistic persona, and body of work are all constantly changing. She likes to be fluid.

For about two years Quattlebaum Jr. identified as a trans woman, using exclusively she/her pronouns in her personal life. Around this time, Quattlebaum Jr. created the persona of Mykki Blanco for a video art project. While he decided not to socially transition and identify (exclusively) as a woman, it is clear that his gendered experience affects his artistic performance today.

For about two years Quattlebaum Jr. identified as a trans woman, using exclusively she/her pronouns in her personal life. Around this time, Quattlebaum Jr. created the persona of Mykki Blanco for a video art project. While he decided not to socially transition and identify (exclusively) as a woman, it is clear that his gendered experience affects his artistic performance today.

“When you’re a trans [woman] but you still have very masculine features, people think they can frown and snarl and look at you as if, ‘How dare you exist?’” Mykki’s experience with trans antagonism has shaped her passion for queering gendered expectations in all of her work. Her music particularly shows her understanding of gender and challenges homo and trans antagonistic norms.

Many of Mykki’s songs discuss gender performativity, and specifically feminine performativity. His hit “Wavvy” is full of gender(queer) references. In the music video, Blanco performs in both a distinctly masculine and a feminine persona. In the back of a van, Mykki spits “Maybe she born with it, maybe it was Maybelline,” a line that implicitly invokes the feminist nature/nurture discourse in a relatable way. Regardless of why she performs gender the way she does, Mykki is implying that it does not matter what she is wearing; what matters is that she is expressing herself in the way she wants to.

As the music video flashes back and forth to feminine Mykki and masculine Mykki we can see the complexity of her gender and how it enhances her music. The video also celebrates both personas, refusing to narrate the masculine persona as fake and the feminine persona as real, or vice versa. In this way, Mykki challenges and queers the dominant trans narrative in which a person transitions from one binary gender (male) to the other (female) in a static manner. Instead, Mykki Blanco is a performer with gender ambiguity, presenting and identifying with both feminine and masculine performance. While she may identify mainly as femme, Mykki also shows that one can be comfortable with “passing” as both masculine and feminine in different situations.

Several more of Mykki’s tracks (in fact, almost all of them) comment on gender norms and trans and homo antagonism. In “Coke White, Starlight,” Mykki opens the track by stating that “They don’t wanna see a man in a dress succeed,” then proceeds to rip her critics apart for their lack of musical talent in comparison to her own. By opening up the song with this statement, she directly challenges critics to think about why they do not support her work; is it because Mykki is not talented or because he challenges hip hop’s ideas of gender?

Mykki’s songs reflect her constant transgression of gender norms by simply existing. She delights in the confusion her (gender and musical) performance causes audiences, repeating in the hook of “New Feelings” that “I, I’m too freaky for n*ggas, yeah / I, I’m too freaky for bitches.” Mykki suggests that her gender performance simply does not fit into the “male” or “female” camp, implicitly referencing a common theme amongst biracial hip hop artists who similarly feel that they are not really white nor black, or at least are not accepted as such. But here Mykki is emphasizing that she does not care that she does not fit into any easy categories; he instead enjoys being too “freaky” for comprehension. In the shockingly underappreciated “Wish U Would (feat. Princess Nokia),” Mykki further underscores his comfort with his fluid gender and its relation to her art by sampling some words from Joanne the Scammer. Scammer is the feminine, comedic counterpart of Branden Miller who performs as female but identifies as male. Scammer’s words are sampled to reflect Mykki’s general apathy towards following predictable gender norms: “You got your own opinion on me? I do not give a fuck what you think.”

Mykki’s songs reflect her constant transgression of gender norms by simply existing. She delights in the confusion her (gender and musical) performance causes audiences, repeating in the hook of “New Feelings” that “I, I’m too freaky for n*ggas, yeah / I, I’m too freaky for bitches.” Mykki suggests that her gender performance simply does not fit into the “male” or “female” camp, implicitly referencing a common theme amongst biracial hip hop artists who similarly feel that they are not really white nor black, or at least are not accepted as such. But here Mykki is emphasizing that she does not care that she does not fit into any easy categories; he instead enjoys being too “freaky” for comprehension. In the shockingly underappreciated “Wish U Would (feat. Princess Nokia),” Mykki further underscores his comfort with his fluid gender and its relation to her art by sampling some words from Joanne the Scammer. Scammer is the feminine, comedic counterpart of Branden Miller who performs as female but identifies as male. Scammer’s words are sampled to reflect Mykki’s general apathy towards following predictable gender norms: “You got your own opinion on me? I do not give a fuck what you think.”

It may seem bizarre that Mykki and other transgressive hip hop artists use a musical genre that has been extensively critiqued by (often white) listeners for being offensive. Namely, critics note that many popular male rappers perpetuate queer antagonism, (trans)misogyny, and other toxic forms of masculinity in their music. That being said, many critiques of hip hop and rap conveniently ignore that issues of queer antagonism and (trans)misogyny occur in multiple genres of music, including the most mainstream hits. Mykki articulated this well in response to an interviewer asking about homophobia in hip hop: “Excuse me, let’s not be racist and target hip-hop! Why is the music business in general so homophobic?”

As Mykki’s statement implies, race is certainly a factor in the critique of hip hop. As a dominantly and original black genre of music, hip hop and its radical nature is

Young Thug’s “Jeffery” Album Cover

unsurprisingly targeted by (namely white) critics for its problems without mention of the many powerful aspects of the music. Take, for example, artists like Kendrick Lamar or the 90’s rappers KRS-One and Public Enemy, all of whom use their art to challenge racism and police brutality. Further, female hip hop or any sort of queer subset of the genre is often particularly empowering without being problematic. Mainstream artists like Young Thug (who wore a gown on one of his album covers and identifies with a third gender) are also publicly changing how listeners understand hip hop in relation to gender today.

Hip hop is a very clever way to challenge the status quo, and it makes sense that artists such as Mykki would be drawn to the rebellious nature of the music. The genre has been said to house a “raw and radical force of Blackness,” a force that is often used to challenge white society through music. Hip hop, unlike many other genres of music, has been directly influenced by the social radicalism of the 1960’s and 70’s; hip hop as a musical genre grew and changed shape as the Black Power movement did the same. Rishma Dhaliwal wrote in I Am Hip Hop Magazine that hip hop “reference[s]…the social conditions of Black people and… guide[s] its listeners through the contemporary problems of urban life.” This genre, then, can be said to be innately political as it currently and historically speaks the truth of racial injustice. Hip hop and rap are therefore logical musical genres to challenge gender norms as well as those concerning race. Mykki’s music therefore uses the powerful radicalism of hip hop to promote a new message: hip hop should challenge white supremacy in a way that does not further oppress queer and trans people of color. On this subject, Mykki told Bullet Media: “When femininity is seen as a source of power in black culture, homophobia will no longer exist.”

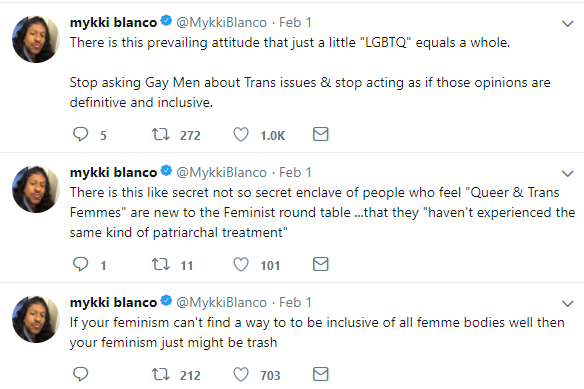

It is important that I include a disclaimer here to say that no genderqueer representation, including that of Mykki Blanco, comes without problems that should be discussed. Mykki, for example, tweeted about bisexuality in a way that seemed to negate the work, struggle, and legitimacy of people who are bisexual. However, he shortly thereafter clarified that he meant famous persons who “outed” themselves as bisexual in order to gain “social justice clout.” She tweeted: “I know that Bisexuality is human, is real is authentic.” She later deleted the account that contained all of those tweets.

I would argue that Mykki’s performance, along with other queer and trans musical artists like her, is a brilliant transgression of gender norms that combines both gender performativity and artistic performativity. Mykki is a hip hop artist who signals that being genderqueer, being fluid and ambiguous, is not only okay, but powerful and beautiful. Mykki’s work challenges mainstream music’s tendency to police peoples’ genders, sexualities, and expressions. In this way, I would argue that Mykki Blanco and Michael David Quattlebaum Jr. are revolutionary. Mykki’s gender performance and fucking with norms is enough to convince me that she is making a true difference in the hip hop world and in mainstream culture, especially in this moment in which trans individuals are receiving unprecedented public attention.

But why does representation matter? In reality, “how trans folks are represented is a matter of life and death.” Many representations of trans folks in media, especially in television and movie productions are intensely problematic. Trans narratives in these stories are often stereotypical (trans people as victims of violence or as sex workers) and at times dangerous (trans characters depicted as violent, scary, pathological, and/or those used as trans antagonistic plot devices). Depictions of trans people as threats and liars has real implications. Representation at times completely shapes non-trans cultural understandings, especially considering only 16% of cisgender people personally know someone who is trans. Further, trans characters are often written and portrayed by non-trans writers and actors, which skews accurate, non-offensive representation of trans folks.

But why does representation matter? In reality, “how trans folks are represented is a matter of life and death.” Many representations of trans folks in media, especially in television and movie productions are intensely problematic. Trans narratives in these stories are often stereotypical (trans people as victims of violence or as sex workers) and at times dangerous (trans characters depicted as violent, scary, pathological, and/or those used as trans antagonistic plot devices). Depictions of trans people as threats and liars has real implications. Representation at times completely shapes non-trans cultural understandings, especially considering only 16% of cisgender people personally know someone who is trans. Further, trans characters are often written and portrayed by non-trans writers and actors, which skews accurate, non-offensive representation of trans folks.

In comparison, I believe there is something powerful about trans self-representation. Just as trans writers are more likely to produce work which appropriately represents real trans lives, trans artists who perform trans-related content are more likely to depict the reality (and thus, variation) of trans identity. Artists like Mykki Blanco celebrate trans and queer identity, often without contributing to the aforementioned problematic aspects of inaccurate representation. Positive, empowering trans visibility in the media could help to (and arguably has) shift cisgender perceptions of trans people. While media representation itself is not the complete answer to combatting trans antagonism, Mykki as a genderqueer representative definitely challenges the hip hop community to rethink gender and its role in the genre. In both his music and his style, Mykki highlights her genderqueer performance. In this way, I think she is truly a great example of an artivist. While her Twitter and Facebook posts and activism alone give her claim to artivism, everything about her musical performance itself challenges cisgender normativity and invites listeners to think outside of the gendered box.

In both his music and his style, Mykki highlights her genderqueer performance. In this way, I think she is truly a great example of an artivist. While her Twitter and Facebook posts and activism alone give her claim to artivism, everything about her musical performance itself challenges cisgender normativity and invites listeners to think outside of the gendered box.

I think it’s really intersting how you explored the intersectionality of hyper masculinity within rap and hip hop culture, as well as homophobic and anti-trans/queer themes that spawn off of that. I think race is an important aspect when analyzing hip hop culture as well, especially mainstream society’s reactions and judgments of it as comsisting of “violent black men”–perhaps building upon Mykki’s intersectional experience of oppression.. Mykki’s unique navigation in the world of hip hop living as a queer and fluid person explicates that music, specifically, has a lot farther to go in accepting varying forms of identity. What might be interesting to look at further (as a connecting topic), is how femininity is rejected by the typical “rapper lifestyle”, as Mykki says. Do you agree with her when he said that accepting feminine expression into hip hop is the gateway for accepting other marginalized identities such as those of queer/trans people? Do you think this applies to other industries and cultures as well?

Hi Hailey,

I think these are super interesting questions. Mykki is a great example (amongst other queer / femme hip hop artists) of the visible change in the hip hop community. I think that even the mainstream genre is changing; artists like Kendrick Lamar are talking more about masculinity and problematic aspects present in hip hop. It is probably reductive to assume that all genres are going to become more accepting of artists with non-normative identities automatically, but I do think that there is a progressive trend in the music industry.

Thanks for posting this! And for introducing me to Mykki! So much of the coverage I’ve seen of gender/sexuality expression in hip hop and rap has been centered only on Tyler the Creator/Frank Ocean/Kevin Abstract, and while those are also important voices, it’s refreshing to consider a genderqueer perspective as well. I love the way Blanco talks about the hypocrisy and racism of calling out homophobia only in hip hop and not in the music industry more generally. It makes me think of the Jacob Hale rules for research and the idea of asking ourselves: what does our interest in a specific research topic or issue tell us about ourselves, rather than what it tells us about what we’re researching. Also, I really appreciate your intentional use of both he/she pronouns. It reminded me a lot of the Nicolazzo reading!

P.S. This is a video I found on Twitter a while back of straight men realizing Kevin Abstract isn’t straight and it’s truly wild please enjoy https://twitter.com/deadlostboy/status/960928879304216577?lang=en

Your writing encompasses all my thoughts on Mykki Blanco and then some. I think Mykki’s work in particular has aided in creating more of a shift for people who look at non-cis/straight hip hop artists to consider how fluid identity can be and how that can shine through art. I find it especially intriguing how Mykki uses whatever pronouns and various gender presentations. I think this works to complicate the narrative that masculine and feminine is an accurate dichotomy and forces people who listen to and watch Mykki to think about the deeper complexities people embody in gender performance. Additionally, I would love to look at non-black POC who are comparable in identity and artistry to Mykki to see how they interact with hip hop and rap as well as how they are received by audiences.

I love Mykki and this article did a great job discussing her in relation to the major themes of our class. It would have been really cool if you’d done more close-reading of her art, especially in how it humanizes gender-queer people instead of making it into a spectacle. I also do take some issue with your statement that “hip hop can challenge the status quo”, since that assumes a white baseline of “status quo” and sort of brushes over the persistent transphobia and toxic masculinity within hip-hop and black communities. Maybe a better way to say it is that youth culture is a great way to subvert cultural assumptions, and hip-hop is a big part of youth culture. Otherwise, I loved the article – and the music, of course.