Native Americans who identify as “Two-Spirit” – or queer, but in a specifically Native way – are a radical presence. According to Daniel Heath Justice, Euro-American society is deeply heteronormative, and its spread to the United States is precedented on the emptiness of the land before contact. Therefore, Native Americans who identify as Two Spirit are a double threat to settler colonialism. Art is a critical tool for Two-Spirit people to resist colonization, because it enables them to assert their presence and take command of the artistic gaze to which they have often been subjected.

The term “Two-Spirit” was created in 1990 to serve as an umbrella term for many Native sexualities and genders, many of which are tribe-specific. At its core, this identity is intersectional, because it subverts the Western tendency to draw a firm line between the lived experiences of ethnicity and sexuality. To understand why the term exists, it helps to know the history involved – and there is a lot of it. Indeed, although the phrase “Two-Spirit” is relatively new, the phenomena it describes are much older. Prior to European contact, many North American tribes had non-binary definitions of gender, encompassing three, four or even more gender identities. These traditional constructions vary greatly from tribe to tribe, but Sabine Lang writes that if any generalizations can be made, a key trend is that the traditional predecessors of Two-Spirit identities tended to care far more about the gender performance of an individual than their sexual engagements. Because of the gender-driven nature of many tribal traditions, the Two-Spirit identity is often characterized as gender-queer first and foremost.

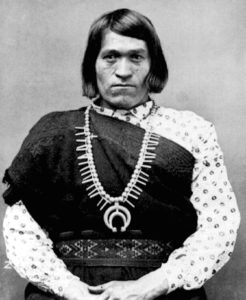

We’wha (1849-1896), of the Zuni nation, who was biologically male but lived as a woman. Source: https://the-numinous.com/native-american-two-spirits/

However, these indigenous forms of gender were greatly damaged by European colonization. When Europeans arrived in the Americas and discovered native people who performed these third-plus gender roles, they lacked the cultural lexicon to understand them. French traders termed Two-Spirit people they found berdache, an Arabic-derived word for “slave” or “kept boy,” and the phrase stuck. These berdache became frequent victims of sexual abuse as Native bodies were eroticized and objectified. There are several recorded cases of white men forcibly taking berdache for the purpose of prostituting them to other white men, thereby literally commodifying them. Along with such violence and abuse, berdache were further marginalized by the imposition of a strictly gendered social and economic model. According to Daniel Heath Justice, as Native American communities were transformed to perform roles in the colonial agricultural economy, the social niche that queer Native Americans once filled began to disappear.

Things began to change again in the 1970s when, thanks to increased national attention to civil rights issues, many movements emerged to empower both Native American and queer people. As a result, academic understandings of the berdache began to evolve, pushed forward by the work of activists and scholars such as Beatrice Medicine, Wesley Thomas, Sue-Ellen Jacobs, and Will Roscoe. In 1990, the term “Two-Spirit” emerged from a conference of queer natives in Winnipeg. Drawing from old tribal stories and cosmologies that figure these people as embodying two genders in one, the term “Two-Spirit” was created to replace berdache, with its colonial origins and degrading implications. The term “Two-Spirit” was meant to represent increased self-determination for queer native people, presenting them not as “slaves” but as individuals embodying both masculine and feminine spirits. In the words of Brian Gilley , “Two-Spirit identity represents a continuation of the ‘berdache tradition,’ but constructed in indigenous terms rather than that of Western ideology.” According to Chapter 6 of this book by Megan MacDonald, Two-Spirit people are also likely to identify as indigenous first, queer second, emphasizing the importance of their experiences as POC.

Over time, this re-framed field of study has become more self-critical, with academics seeking more interaction with – and input from – contemporary Two-Spirit people. One of the critical developments in this field of study is the increasing value given to Two-Spirit individuals as makers of knowledge and theory, rather than passive subjects for settler anthropologists to mine for information. New more inclusive approaches to research and criticism have continued to develop with an emphasis on direct engagement with Two-Spirit People. Andrea Smith suggests that scholars focus less on Two-Spirit people as a subject of study, because this perspective reduces the complexities of their lives to a consumable object or image. Instead, she recommends using Native and queer perspectives to interrogate settler colonialism. In other words, the ability that Two-Spirit people have to create knowledge is radically potent.

This concept of empowerment through creation is echoed and transformed in an an essay by Natalie Diaz, who writes that in making art, indigenous people create art, they express their desires, their perspectives and their presence. These things fight erasure while digesting the complex layers of modern Two-Spirit identity, which is the product of two conflicting Americas, traditional and uncolonized. Diaz writes that “America did not crush us when it devoured us, but became us, as we became it – indigenous art nourishes the country from within.” She gives the example of a mural called “For the Pride of your Hometown, the Way of the Elders, and in Memory of the Forgotten” by the Oaxacan artist collective Tlacolulokos. She says this mural “frees the indigenous body from the margins of Los Angeles history, from subservience to the conquistador, and places it back in the center.”

Building on this, it is inherently subversive for Two-Spirit people – being both indigenous and queer – to voice their desires, beliefs and feelings through art. Diaz is not alone in this. One study has found that “Two-Spirit artists’ work confronts heteronormativity by exhibiting shifts in gender roles across cultures and time and embodying the values of community organizing, storytelling, and survival.” In other words, their work is critical to the formation of an anticolonial culture.

Within queer and native scholarship, Diaz’s narrative about reclaiming the body by expressing It echoes the work of Qwo-Li Driskill, a Two-Spirit poet and scholar who has written about the power dynamics of creating art. In the linked article, they posit that the white gaze wants to colonize, control and passively eroticize Two-Spirit bodies, and their representations of the Two-Spirit person reflect this. Flipped, this means that for a Two-Spirit person to represent their own sexuality or their gender identity is an act of resistance. This is a powerful sentiment because it critically conveys that engaging in narrative is transformative. All artistic expression works to form a narrative of some kind, and this narrative can be very powerful when placed in conversation with others; considered together, Smith, Cooper, Diaz and Driskill suggest that this is especially true for Two-Spirit Artists.

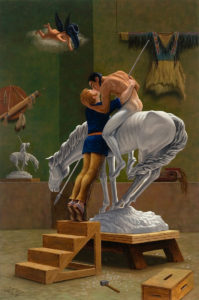

“Icon for a New Empire” by Kent Monkman

In the article above, they describe how they are journeying towards a “sovereign erotic” through writing, and highlights the healing power of both writing and sharing stories. Narrative engagement is one of the most powerful tools available to Two-Spirit artists across all media. Kent Monkman (Cree) is a clear example of a Two-Spirit artist whose work is deeply engaged with narrative. Many of his paintings criticize the egocentrism of the Europeans who devised the concept of the berdache, and the paint to the left, titled “Icon for a New Empire,” is one case of this. Painted in a grotesque parody of European Renaissance art, the painting alludes to the Greek myth of the artist who fell in love with his work. Here, the white artist gives life to his sculpture of the idealized macho Native American – naked and stoic on horseback, ready to be outfitted in the cliched native costumes seen on the wall. The painting captures the way that colonizers create a specific idea of the colonized, one that they fetishize and favor over reality. The homoeroticism of the white artist in the painting is especially important because of how it alludes to the objectifying nature of many fantasies about Native Americans, which Justice points out are often deeply queer in their fascination with a certain breed of hyper-macho stoicism. The white man creates an object of erotic desire from the “marble” of the Native American, who – like in the Trexler account – are only represented as tokens of desire for white men. The colonial mindset cannot even portray Two-Spirit people negatively, because to do so is to acknowledge their agency, in a way. But settler colonialism demands that if there is anything outside of the colonial norm, it must be destroyed or made into something owned by white men.

Kent Monkman as Miss Chief: Justice of the PIece. Potomac Atrium, NMAI Mall Museum.

Monkman also has a drag persona, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, which celebrates the duality of the Two-Spirit identity and how it is distinct from mainstream queerness. For example, Miss Chief uses female pronouns, wears makeup and jewelry, like most drag queens, but her costume is not particularly dedicated to emulating or exaggerating feminine traits. With a visibly masculine pelvis and an exaggerated bead necklace covering a flat, uncontoured chest, the visual of Miss Chief is arrestingly queer in a way that challenges the tropes of mainstream, white-dominated drag. In figure B, Miss Chief holds court in a performance at the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. The visual spectacle of a “man in a dress” meets that of the cliched Native American chief, both marginalized caricatures, and yet it is placed – paradoxically – at the height of respect in the Anglo-American legal system, as a judge. This is another example of Two-Spirit art that radically subverts colonial power structures.

Art can enable Two-Spirit people to defend and heal their bodies from objectification and degradation while asserting their continued presence. Indeed, the very act of making art can empower individuals and build community, regardless of whether and how that art is consumed. For example, in an interview with CBC News, Massey Whiteknife, a Two-Spirit businessman known for his drag person ICEIS Rain, describes what performing the character has done for him personally: “I was becoming somebody I wanted to become through ICEIS Rain…[I] realized that ICEIS RAIN was teaching Massey to be stronger and stand up for himself and face those fears, but of course, while still continuing to work.” His words emphasize the healing power of art for the artist as well as those who consume the art. Like Driskill writes, expressing and experimenting freely with his gender identity has enabled Whiteknife to form an independent voice.

Art can function like this in a community setting. For example, there is an annual gathering for Two-Spirit people in Minnesota, often called the Basket and the Bow. This gathering, which was named after a Navajo tradition whereby young children were allowed to choose how they would be gendered, was first held in Minnesota in 1988, and it has continued to meet once a year for a week. This gathering gives Two-Spirit individuals a chance to gather and participate in communal activities like beading, camping, teaching, drumming and dancing. These activities are not just social – many provide creative outlets as well. Critically, the Basket and the Bow was and is closed off to non-Two Spirit people, marking it as an event by and for the community. This is an example of social and creative action forming resistance without ever presenting itself as a consumable subject to the outside world.

Two-Spirit art demonstrates that the very act of creation is empowering. It resists the myriad forces that have tried to steal, degrade, distort and silence Two-Spirit people and their histories, even if all it does is exist – because it asserts the presence of Two-Spirit people. And this is critical. Being Two-Spirit is connected to the traditions of the past, but the verb “being” is in present-tense. Art is a way of un-erasing; in some sense it says, “I am here, I have a pen, and here is what I can do with it.”

I really like this article! I liked how you tied together art, race and sexuality in a cultural context. It’s so important to remember how many intersections there are here, which is extremely important in these conversations. I also liked how you emphasized the act of making art as empowerment for the artist instead of for consumption by others as the main purpose. I also really appreciated your connection between the act of maintaining a tradition and bringing it into the present and the act of being.

I think a lot of times even when we talk about intersectional queerness we think that means – or rather, we unintentionally make it mean- taking into account other intersections that exist within our own culture. It makes me think about how things would be different if intersectionality also took into account other cultures ideas and expressions of queerness.