Introduction

The next time you decide to comment “YAS QUEEN” on your best friend’s particularly stunning selfie, stop and thank a drag performer. It’s necessary to acknowledge the contributions drag performers have made towards the greater mainstream culture. Even though drag performance has been considered a subculture, I constantly see its influence in modern vernacular, dance, style, and nearly every aspect of popular culture that we know of today. I am interested in a certain type of drag performance centered on the black and brown queer people who popularized drag balls. I want to know their history. These events in addition to being a performative outlet, were a method of community and network building for marginalized individuals. Drag performers of the 20th century and today are participants in not only a cultural phenomenon, but a political statement that disrupts the preconceived ideas about gender presentation and kinship. I worry that because drag culture has become so ingrained in many spheres, we may lose the true social and political significance of the artform. If we are more than comfortable co-opting their culture, we should just as easily understand the history. By blindly adopting the aesthetics of drag and ball culture, we are, in a way, erasing a legacy built by Queer and Trans* POC.

What is a Drag Ball?

Everyone knows RuPaul’s Drag Race, but what came before it? What existed in the shadows before the glitz and glam of the 21st-century? Drag balls. These are characterized as large competitions in which drag performers dance and walk for judges and a captivated audience. Performers dress according to theme and are tasked with embodying it in their performance while also wowing the crowd with their dance/movement abilities. Such themes may include “Butch Queen”, “Bizarre”, or “Sex Siren” and whoever embodies them best wins the competition. Performers may compete solo, but they represent larger drag houses. These houses are led by a matriarch of sorts who serves not only to be a mentor in the performance sphere, but often these heads of houses also shelter and protect younger participants who would otherwise be living on the streets.

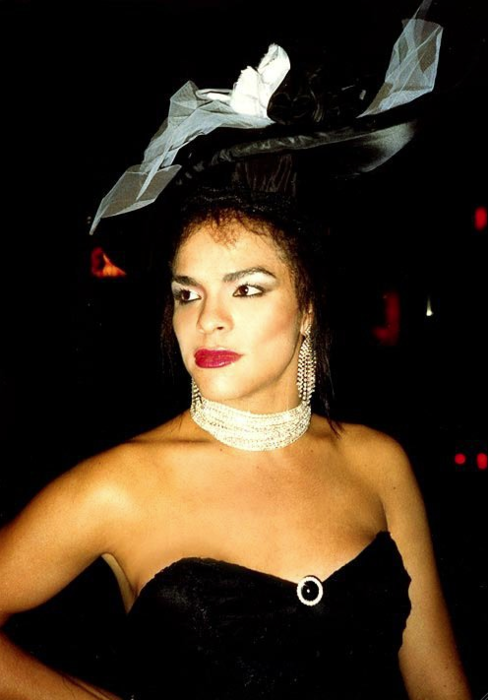

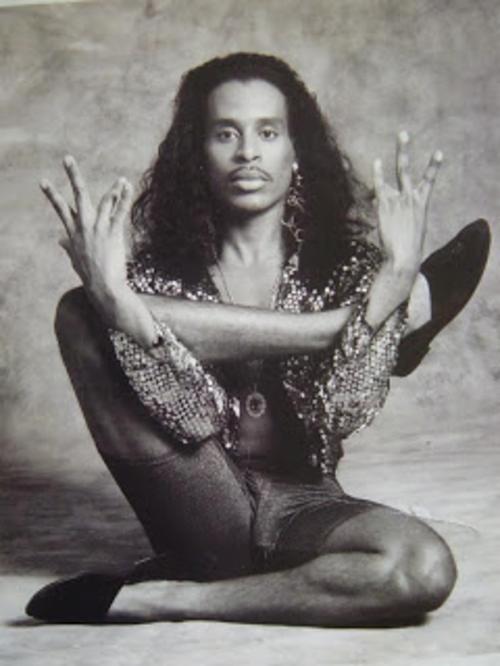

(Pepper LaBeija: House of LaBeija, Angie Xtravaganza: House of Xtravaganza, Willi Ninja: House of Ninja)

Drag balls are not a thing of the past. Queer and trans+ POC still find solace in performing and competing against each other in this way, though I would say that the urgency ball culture had at its peak of popularity has diminished. However, the desire, or need, for space is ever present. The classic, and culturally significant, film Paris is Burning is a fantastic study of ball culture’s rise to prominence and documents the connections and communities formed.

The Beginnings

Surprisingly, drag balls weren’t always spaces exclusively for black and brown queer people. I was working under the assumption that these performances were a specific production of 1980s New York, but that isn’t the case. Ball culture as we (I) know it was formed in reaction to a similar practice which was designated solely for white gay males. The space wasn’t accessible to the queer POC who would later popularize drag performance and balls in the latter half of the 20th century. At its inception, drag balls were an opportunity for the collective performance of gender variance for white men. At these events, competitions weren’t had, but this was a chance for men to dress in drag and put together fashion shows for their community. Something that most definitely differentiates these early balls with the concept we know of today is the overtly racist nature of these events. Apparently, if black and brown drag queens wanted to join in on the festivities, they must lighten their skin. Whiteness, or perceived whiteness, was a stipulation for joining in on a queer space. This is of particular interest for me coming from a performance background. It says something about the way we as a society perform gender and race. In this case, one cannot perform gender or gender variance without also performing a perverted idea of what race is.

In response the the exclusionary policies within the traditional structure of drag balls, black and brown queer and trans folks decided to create their own community spaces in which they could perform gender and sexuality removed from the dominant white population. The roots of drag balls as we know now came about in the 1960s and 70s. The practice became a way to protect the community while also giving young queer people their own space to express themselves.

Cultural Significance

I, as a 20 year old woman, can’t remember a time in which the impact of drag wasn’t felt in my life. This could possibly be due to my curiosity and experimentation with queerness from childhood, but may also be because drag culture has infiltrated the mainstream. We can automatically point to one of the biggest cultural productions from drag culture, RuPaul’s Drag Race as a clear example of contemporary drag performance. For many, this is their first entrance point to anything related to drag culture. While we can of course look at this show and the exposure it has given to this aspect of the queer community, it remains important to understand that this show does not exist in a vacuum. Drag performers have long existed and the credit we give Drag Race is actually due to the performers that came before them, from the popular ball culture in the 80s. Instead of crediting the white, cis, gay men (who may themselves perform drag) we must recognize that our vernacular comes from black and latinx folks. Attributing certain language to the correct populations may seem miniscule, the fact remains that when these people are so marginalized, it’s worth crediting them when possible.

Here are some words/phrases that have roots in Queer POCs:

Shade, Tea, Realness, Reading, Serving, Gurl, (the) Gag, and so much more

What Does Drag Do?

Drag is performance. Drag is security. Drag is family. Drag is political. I think about what it means to form a network and the inherently political nature of community building. To form a collective, in this case a drag house or family, we are confronting social constructions of kinship and family. Additionally, the act of drag was, and remains, a way to keep black and brown people off of the street and temporarily removed from a culture of surveillance that is only meant to further disenfranchise them. In America there is a narrowly defined idea of what makes a family. In its most simple form a family is meant to be a unit built upon blood, but these practices of creating a drag family completely subverts that. It forms a bond built upon love, connection, and communal safety instead of one built on obligation. Additionally, these performers are at a higher risk of experiencing violence, drug abuse, and homelessness. Their racial identities in conjunction with gender and sexuality have created an embodiment of marginalization in America. Drag forms a sense of accountability that wouldn’t exist if these people remained in a position of subalternity. What ball culture has given queer folks generations from its inception is a network of people to whom they are accountable for, in the idea that performers “look out for their own”. A connection born out of mutual desire to be seen and heard, rather than tossed aside by the mainstream, is what these drag houses within ball culture offer.

While it’s natural to be interested in drag culture, it’s also important to know the true significance of the performance. Every ball, drag brunch, tv show isn’t solely for mainstream (cis, white, straight) consumption. The roots of this art are in subjection, marginalization, and need. The drag performance that we see today still echoes back to years in which gender and sexuality weren’t talked about. At the core, it’s important to remember that this culture wasn’t made for us-we are a secondary audience. I’m advocating for a more holistic approach to consuming drag culture in which people still feel comfortable using whatever vernacular, style they chose, but with reverence towards those that came before us and the challenges they had to face.

Yes, wow I loved how you recognized the history behind our mainstream millennial slang, as well as behind RuPaul. Even drag culture that is appreciated in mainstream culture has so much intersectional oppression tied into it, an aspect that is not always delved into on TV shows or in conversations about drag. I think it’s really interesting that before the era of Paris Is Burning, balls were held by white men–exemplifying how important these spaces were/are for people of color who want to participate, because they have been historically excluded. It would be worth it, I think, to investigate drag culture and drag communities and their relationship with trans communities who don’t participate in drag–because I know there has been some tension there. Awesome job!!

I love this post wow!! Thank you for bringing attention to the importance and legacy of POC and Trans* performers before us that paved the way for modern representation. So much of mainstream pop culture fails to give recognition to its creators, even thinking about something as seemingly small as slang words used on Twitter or Vine that were popularized by young people of color, or I’m even thinking about how the work of black feminists like Kimberle Crenshaw and her concept of “intersectionality” is so overused and taken out of context as a buzzword in mainstream feminism. Thank you for introducing us to this history of drag culture, and I hope that I can apply the holistic approach you mentioned to my future appreciation of pop culture, art, and performance.

I loved this blog post! I particularly liked your connection between race and drag balls, I had no idea that they got their start with racist connotations because I’ve only known them from the ball scene in New York. I like your point about recognizing the origins of a lot of the words and phrases of queer culture, it’s important to realize where they got their start. Sometimes I wonder if everyone recognized that these terms came from black, queer/trans, drag queens that there might be a little less prejudice in the world. There’s so much more to drag that just Drag Race and I’m so glad you gave us a glimpse into that! Also, I just have to say that I am a forever fan of the House of LaBeija. Great job!!

I appreciate the voice you give to the whiteness of performing in drag, even in predominantly black and brown spaces. This, at least in my opinion as someone who’s (only a little) familiar with makeup, seems to be an elephant in the room in the modern day watching how skin tones may not match up for many darker-skinned queens (and many lighter-skinned ones). It can be a touchy subject, especially when considering how with makeup one has to lighten certain parts of their face and darken others to give a contoured effect, but I think it’s still one worth talking about, and starting at its roots how you brought it up seems like a great way to do it. When reading about how houses and balls keep people off the streets, it reminds me also that these spaces keep particularly feminine men, trans femmes and trans women together in their own communities. Drag becomes a space where, in addition to having a type of family or kinship, one can express trans identity through performing drag. Especially since drag kings and cisgender queens/kings performing as the genders they identify with are becoming more visible in today’s world, I think it’s important to recognize how drag provides security for trans people in ways that cis people often take for granted. I think that also adds to your argument about how language of black and brown drag queens is often appropriated by white/cis/straight people for their own entertainment.

I loved this article, especially the way you brought attention to the fact that we need to remember where we get some of our popular slang from – queer POC. I also really liked what you wrote about the concept of family; there is a pretty narrow idea of what “family” means but for many communities the created idea of family is so much stronger and more influential to our lives than the family we are born with. I also this using this concept of family to describe communities like the drag community emphasizes the importance of the community to the people who belong to it. Great job!

This is a wonderful article! I love how you grounded all of your statements in an awareness of your own position. You write eloquently about the significance of drag, towards a resolution that is both powerful and balanced. As others have said, I’m glad that you engaged the race history here; a lot of people talk the intersectionality talk, but you walked it effortlessly. Great work!