Image courtesy of Facebook

How do we define what it means to be trans*? Often, trans* people are defined against cis people. Being cis is presented as what is normalized and understood, while being trans* is presented as something that must be explained. This places an unfair and unequal burden on trans* people to explicitly articulate and explain their identities in a way cis people are never asked to. Trans* people are usually asked not just to explain, but also to justify the validity of their identity. Historically, attempts to interrogate and regulate the bodies of trans* people have manifested themselves in laws against cross-dressing, denying civil rights, and withholding proper medical care. Joanne Meyerowitz writes about the history of doctors forcing trans* individuals to present a certain narrative or fit within specific categorizations of gender to receive adequate treatment. Stringent expectations were forced upon trans* people to the point that by the end of the 1960s “transsexuals regularly shaped their life histories and even fabricated stories that might convince doctors to help them” (How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality in the United States, 161). More recently, people like trans-exclusionary radical feminists (TERFs) have attempted to force trans* people to conform to narrow definitions of manhood and womanhood and “prove” those identities, to be included in activist movements. Thinking about this double standard can be useful for thinking about how we conceptualize gender and how we can embrace rather than reject a diversity of gender identities.

Acknowledging and honoring the diversity of trans* experiences begins by examining the treatment of trans* people and the expectations placed on them in everything from TV interviews to daily interactions. As college students interested in gender justice and activism, we wanted to further understand this topic and engage some of our local community in it as well. To do so, we selected four cis-identifying individuals at William & Mary to interview with questions about their gender that trans* people are normally asked. The interviewees all were shocked, surprised, and contemplative in their answers to our questions. They were forced to think for the first time about these things while engaging in a dialogue about them. We purposefully wanted to put them in an uncomfortable position of talking about gender in terms of their sexuality and their relationships both with themselves as well as with others.

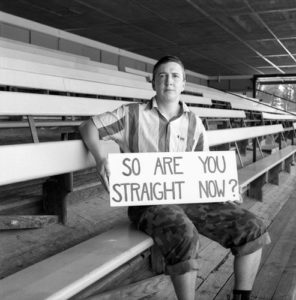

Images by L. Weingarten

These interviews also brought out how we make trans* people into spectacles with the sorts of questions they are commonly asked. We chose specific questions to elicit the double standard in how open trans* people are expected to be about their personal lives as well as how their lives are sensationalized in the media and considered to be subject to public consumption. We aren’t the first ones to do a project like this, asking these sorts of questions to examine how we talk about gender differently with cis and trans* people. Photographer L. Weingarten put together a series of portraits of trans* people holding up signs with invasive questions they are commonly asked. This photography project is meant to “prompt viewers to cast a reflective eye upon themselves, revealing how invasive this questioning can be.” In a more direct way of addressing this issue, transgender author and activist Janet Mock held an interview with Alicia Mendez in which Mock assumed the role of the interviewer and asked Mendez, a cisgender woman, a series of invasive questions. Mock wrote: “[m]y job was to interrogate her with questions about her body and her identity so that I could enlighten and educate my viewers, assuaging their curiosities and fulfilling their fantasies about cisgender people, ensuring at the end of our interview that she had proven her womanhood to me and my audience.” The use of the word “fantasies” in this quote leads one to understand that trans* people exist as sorts of erotic, fantastical beings in the eyes of others. This dehumanizes trans* people, objectifying them as deeply not ‘normal’ or acceptable. Mock elaborates on her intent to reveal the invasive nature of these questions by saying, “[y]ou see her transform from confident interviewer and host to a cowering young woman, protecting her body from my line of questions. This is what happens when we dehumanize and other individuals. We strip them of agency, we put them on display, we ask them to speak on behalf of whole communities, we tokenize them, as Alicia pointed out.” By changing the focus from interrogating trans* identity to interrogating cis identity, we hoped to raise questions about how gender is constructed and undermine normalized assumptions of what it means to be cis.

We began interviews with a quick introduction and letting the interviewees know they could take a break at any time or feel free not to answer, and ended each interview with a quick debrief of the project motivation. We interviewed four college students: C, X, H, and S. We knew all four of them before starting this project and chose to interview them specifically due to the diversity of their experiences and of their familiarity, or rather lack thereof, with gender and sexuality studies. We asked them each the following questions:

- Can you introduce yourself? (age, gender, etc)

- How often do you think about gender?

- So you have a ‘gender identity’?

- When did you become a man/a woman? Did you always know?

- What are the bounds of gender identity? So are you saying that someone’s ‘gender identity’ can be anything? Like they could identify as a tree or an espresso?

- How do you date? How has being cisgender affected your romantic life?

- When did you decide to be your gender?

- What if you change your mind?

- If you decided to be a [other binary gender], would you be gay or straight?

- How well do you think that you ‘pass’ as a man/woman?

- How often do you get misgendered?

- What’s the worst thing a trans* person has ever said to you?

- What do you want trans* people to understand about cis people?

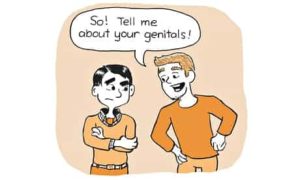

Image by Bill Roundy

The deeply personal nature of these questions threw off all four of our interviewees, and sometimes gave way to defensive responses. It became clear when a question made an interviewee uncomfortable because they would answer with “I don’t know enough” or “I don’t have the authority to talk about this.” X (20, identifies as male) gave the shortest answers of all the interviewees, and was very much caught off guard by questions such as the one about whether he would be gay or straight if he were a woman (“No idea. Wow. That’s a tough question. I don’t know if I’m in a position where I could answer that because I feel like… I just… I don’t know I feel like it’s not my place to answer that question. I don’t know enough”). S (20, identifies as male) and H (20, identifies as female) both expressed that some questions caused them to rethink their assumptions about their own gender identity and sexuality. When asked about his romantic life, S noted “that is such a good question, because [being cisgender] does inform the way I go about pursuing romantic interests” in ways he hadn’t thought about before. With this, we saw a variety of responses from our interviewees. They were thrown off in different directions, some expressively questioning themselves on the spot, and some standing their ground without taking a step back.

There was a tendency to treat gender identity, biological sex, and sexual orientation as directly related in some ways. When asked about how his sexual orientation could change if he were a woman, S admitted his reflexive response to associate womanhood with biology: “If I decided to be a woman? Um… I don’t know. I think I would do whatever my body told me to do. Ah okay so there I just gendered myself as a woman because I thought of myself as having different reproductive organs.” As for gender identity, H was the only interviewee to pinpoint an exact moment she felt that she “became” her gender and furthermore, she associated this moment of becoming a woman with a biological determinant, the beginning of menstruation, and talked about the cultural meaning surrounding that as well.

This also speaks to how all our interviewees understood their own gender identity as something externally assigned to them and how they fulfilled certain notions of physical presentation and gender roles. When asked to elaborate on her gender identity, H said simply: “Society taught me to feel a way about biological and physical aspects that apparently define gender for me.” C (20, identifies as female) talked about the clothing and toys she received as a child and how other people’s perception of her shaped her identity: “I guess you could say I look more feminine, and so I was treated as a woman. I think I never had a problem with that, I guess it always kind of fit for me, that definition people were putting on me.” When asked about passing, X expressed confidence in his gender identity and that he didn’t care what other people interpreted that as, but also noted that he has “never been misgendered.” H said that even though she has been misgendered as a man on several occasions, she has never been bothered by it because “people have very rigid notions of how people on either side of the gender spectrum should look and behave.” S touched on these expectations and gender roles in his answer, attributing the times he’s been misgendered as a woman at drive-thrus partially to his personable demeanor and conversationalism, something that isn’t always expected of men. In all of their answers, they expressed the role other people’s perceptions of them played in how they expressed and understood themselves.

At the same time, there was a willingness to think about gender as a fluid construct and to interrogate their own identities. All four interviewees initially said they felt gender identity was boundless, and expressed hesitation but open-mindedness to follow-up questions about whether or not someone could identify as a tree or a coffee bean. All four were also very receptive to the notion that they might one day change their minds about their gender identity. H said: “My sexuality is fluid, my gender could be fluid in the future.” C talked about how she would inform other people and might alter her “physical appearance to better represent the gender I identify with.” X noted that while exploration of a different gender identity “would be scary…discovering that new aspect of my personality could be cool.” S likened the process to video games:

“When you start, you get a character, right, that’s like it’s made for you. And then you get to that point in the game where you can customize it and you’re like “oh, I have options.” And I think that’s kind of when I realized if I am a man like everyone’s been saying, then I need to create that for myself. And fit myself into that as I see fit.”

Image by Bill Roundy

The most consistent answers we received were to the final two questions. Not only did every interviewee say they couldn’t think of a time when a trans* person had ever said something bad to them, but could not think of anything they wanted trans* people to understand about cis people other than an apology. As C put it, “I feel like there are not a whole lot of misunderstandings for cis people,” and all four acknowledged that in fact cis people probably have more to learn about gender from trans* people than the other way around. They also expressed apologies for their lack of knowledge and a willingness to learn more about the experiences of trans* people. H summarized this idea well, saying: “Sorry we’re the worst. I think a lot of us are trying. Sorry it takes so long. We’re working on it.”

These interviews revealed almost exactly what we set out for them to do in the first place – display the differences in how cis people answer questions that trans* people are often asked. None of our interviewees were prepared for these questions where trans* people are expected to be prepared at any given moment. We hope these interviews continue to inspire new questions. How do we think about gender? Are we talking about it in the wrong way when we talk about it in an essentialist & binary way? Is it a problem that people have trouble conveying their genders with words? Do we expect trans* people to fix this for cis people? These are all questions that everyone needs to ask themselves in order to understand the cis/trans* dichotomy, because we all need to understand gender if there’s any hope of dismantling patriarchy. This begins with respecting trans* people and their knowledge as well as learning to ask questions in a respectful way. There is so much to learn from the nuanced understandings of gender that trans* people embody through their own experiences. TERFs and other trans*-antagonistic individuals could surely benefit from this invaluable knowledge, but we can’t learn if we continue to dehumanize and other trans* identities. Only through mutual understanding and cooperation can we move towards gender justice.

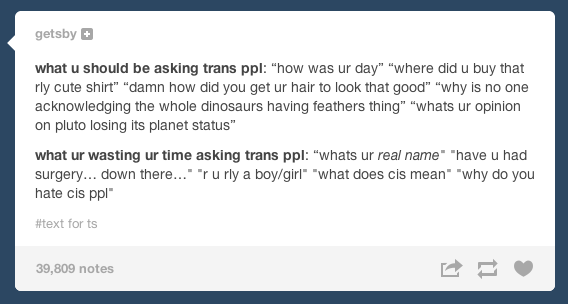

Image courtesy of pinterest

One more thing: stop asking trans* people these invasive questions. Ask them about their favorite color and whether or not they think pineapple belongs on pizza.

Written in collaboration with Emily Mudd

Speak Your Mind