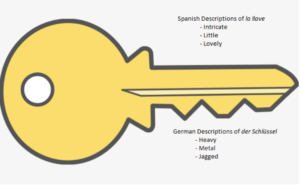

“To continue with the German genders: a tree is male, its buds are female, its leaves are neuter; horses are sexless, dogs are male, cats are female — tomcats included, of course; a person’s mouth, neck, bosom, elbows, fingers, nails, feet, and body are of the male sex, and his head is male or neuter according to the word selected to signify it, and not according to the sex of the individual who wears it — for in Germany all the women either male heads or sexless ones; a person’s nose, lips, shoulders, breast, hands, and toes are of the female sex; and his hair, ears, eyes, chin, legs, knees, heart, and conscience haven’t any sex at all. The inventor of the language probably got what he knew about a conscience from hearsay.” – Mark Twain, “The Awful German Language”

Introduction

The constructions of language and gender are both central to the existence and prosperity of modern societies, however we seldom consider the ways in which they work together to perpetuate existing institutions of oppression, most notably the gender binary. The ubiquity of gender in language poses several issues regarding the future of gender and how it is understood and recognized globally. As gender becomes a more and more fluid means of identification, it remains constrained by the language and subsequent cultural context in which it is interpreted. Languages with a strong connection to gender, whether it be through assigning genders to nouns, pronouns, reflexive verbs, or some combination of those, reinforce the concept of compulsory heterogenderism and thus the marginalization of trans* people and people that identify outside of the gender binary. Having the proper terms to express, recognize, and represent a diverse array of gender identities is invaluable to a society and its posterity. How can one feel as though their gender identity is valid and recognizable by others if words to describe it do not even exist in their native language?

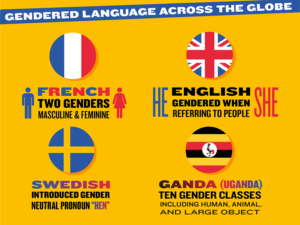

According to the article The Gendering of Languages (and as seen in some examples above), every language that currently exists distinguishes between the genders in some manner, however the role gender plays in any particular language depends on if it is classified as a grammatically gendered, genderless, or natural gender language. Throughout this post, we will explore the detrimental nature of heavily grammatically gendered languages and evaluate the merit or natural gender and genderless languages.

Grammatical Gender and its Oppressive Implications

Although it may appear as though all languages are grammatically gendered, this is not the case. All languages include words to communicate the idea of gender, at the very least in terms of a binary understanding, however not all languages have been constructed on a foundation of gendered nouns. Two of the most prominent grammatically gendered languages are French and Spanish, similarly structured Romance languages that utilize gender as an essential means of categorizing their words. For example, in order to communicate the phrase “I need the salt” in Spanish, you must say “Yo necesito la sal.” The “la,” the feminine definite article in the Spanish language, indicates the gender of the word. In English, a natural gender language, there is only one definite article — the word “the.” When you are describing a particular object in English, like “the salt,” the salt has no inherently prescribed gender. The use of gendered nouns serves as the primary distinction between grammatically gendered and natural gender languages.

The intrinsic incorporation of binary gender into grammatically gendered languages contributes greatly to the reinforcement of the gender binary and compulsory heterogenderism within the cultural contexts in which they are spoken, exemplified in some manner by the picture above. Compulsory heterogenderism is also detrimental to boys in creating stereotypes against them, shown by this video. As Stephanie Pappas noticed, researchers from the Sex Roles journal found that “countries where gendered languages are spoken ranked lowest on the scale of gender equality.” Although the relationship between language and gender equality is noteworthy, there is certainly not a perfect correlation between the two. According to the article Bucking the Linguistic Binary, languages, despite being particularly stringent institutions, are often “used according to shared public consensus” and not “decided by an authority,” meaning that to a certain extent, languages are adaptable to the societies and communities in which they are spoken and thus do not always create rigid or predictable outcomes in terms of gender equality. In fact, grammatically gendered languages are not the only languages that perpetuate oppressive understandings of gender and sexuality; neither natural gender nor genderless languages are immune to bolstering such conditions.

Alternatives to Grammatical Gender and their Merit

Aside from gendered languages, such as Spanish and French, there are two other distinctive categories of languages in terms of gender — natural gender and genderless languages. Natural gender languages do not usually classify non-animal or non-human nouns as either male or female, whereas genderless languages do not classify any nouns as being either masculine or feminine. Natural gender languages, like English and Swedish, still have a compelling connection to gender, however it is less pervasive than that of grammatically gendered languages. The difference, though, lies in the fact that it is possible to “challenge these parameters” and utilize gender neutral terms, as seen in personal stories from an article in The Establishment.

A major issue that arises within natural gender languages is the matter of gender asymmetry. Gender asymmetry refers to when gender is needlessly lexically marked. An example of this, again referencing The Gendering of Language, is the term “stewardess”; it becomes a term entirely separate of “steward” and takes on a new meaning — “a female steward.” As a result, “steward” becomes falsely recognized as the neutral form of the word.

Genderless languages, in addition to not categorizing any nouns as masculine or feminine, feature a single, genderless pronoun that is used in reference to humans. Estonian, an example of such a language, only has one genderless pronoun (“tema”) that serves as an effective replacement for the English words “he” and “she,” again from The Establishment article. The existence of a single pronoun allows for people to address each other without having to assume a particular gender identity of them; this endorses more respectful, open communication amongst Estonian speakers and speakers of other genderless languages, like Chinese and Finnish. Despite being inherently more inclusive of those who identify outside the gender binary, genderless languages still do not result in egalitarian, model societies. In terms of fostering environments of gender equality, Pappas found that genderless languages shockingly “didn’t fare as well as natural languages… (though they did fare better than gendered languages).”

The Push for Linguistic Neutralization and its Backlash

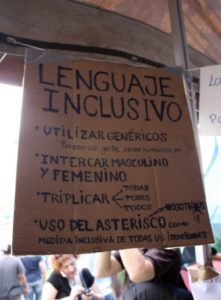

Author of Bucking the Linguistic Binary, Levi C. R. Hord, found that a strong desire to neutralize languages has been adopted by both feminists seeking to increase gender equality as well as trans* people “who seek a language that will aid them in expressing identities that fall outside of the binary genders of male and female.” The politics of language are particularly contentious in our current political climate, however are arguably more important than ever. The ability to have words with which to properly articulate and represent your personal lived experience, as well as the lived experiences of others is extraordinarily valuable.

For example, there have been specific movements to add gender neutral pronouns to the French language. “Os” and “lo” have been some proposed additions to the French language as pronouns and terms for non-binary people. However, after the push for gender neutrality in French, the Académie Frasçaise said that as France is:

“Faced with this ‘inclusive’ aberration, the French language is now in mortal danger.”

The mainly old, white, and male Academy that rules on matters pertaining to the French language is nowhere close to accepting gender neutral additions to the French language.

Spanish, as another Romance language, has similar problems with inclusive language.

It is important to note that although there is considerable support in both feminist and queer circles towards the neutralization of languages, there is a countermovement against it within certain trans* communities. The “movement towards neutral language… in transgender communities is sometimes viewed negatively by older (usually binary gendered) transgender people” because they devoted extraordinary time and effort to the legitimation of the gender binary, as described in Kate Bornstein and S. Bear Bergman’s book, Gender Outlaws.

Conclusion

The push for linguistic neutrality is an important, though not as focused on, aspect of the fight for equality within the trans* community. Language is an aspect of life that is used everyday, yet maybe that is the downfall of the trans* community not noticing it. The long standing gender norms that lie within gender go uncontested because that is the language we are taught from such a young age, and people do try to go against it for fear of being confused by other people. Gender neutralization of language will not only help trans* and non-binary people be validated in their identity, but help to break down overarching gender norms in language reinforced by day to day communication.

By: Baldeep Kaur, Sami Pabley, and Ryan Glover

Speak Your Mind