What issues do trans* people face today?

The United States is considered to be a “first world” country, but two in five Americans live in a state of economic insecurity. This statistic demonstrates to us that close to half the population of our country is struggling financially— a significant number for a “developed country.” In some ways, this statistic is a useful one. Statistics which generalize about the economic status of the population provide information about how the country has improved or worsened over time. They help politicians, legislators, activists, and your average citizens to get a sense of how the country is performing, and which policies are working and which are not.

However, this broad statistic is incomplete as it fails to recognize that some individuals experience these struggles disproportionately more than others and at heightened rates. Without proper acknowledgement of the intersectionality of poverty in the United States, this statistic only tells only a fraction of the larger story. It is vital to have this whole story and the intricacies that it contains if we are to begin to take significant steps towards alleviating and eradicating poverty. Although poverty is a problem for many different people, different steps, different activism and different legislation is needed to solve this puzzle.

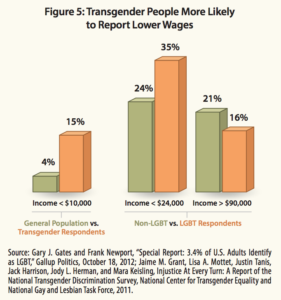

A recent report found that trans* people are nearly four times more likely to live in poverty than the population as a whole, despite the fact that statistics also show that 87% of trans* people have completed at least some college and 47% have obtained a college or graduate degree. These rates are much higher than the general population, yet trans* individuals are still significantly poorer than cisgender people. Furthermore, even this statistic only gives us one slice of the pie because trans* people of color report rates of poverty at even higher rates. These numbers prove that simply being trans* comes with a financial penalty, which is compounded by other intersecting forms of discrimination.

It is also important to acknowledge that employment is incredibly difficult for many trans* people to reach. Before focusing on trans* discrimination in the workplace and what could be done to help those struggling within the space, it is important to take the the time to acknowledge those who are outside of the opportunities afforded to middle-class trans* people. The National Transgender Discrimination Survey (2011) found that the unemployment rate for transgender workers was twice the rate for the population as a whole (14% compared to 7%). Furthermore the rate for transgender people of color reaching as high as four times the national unemployment rate. (p. 3) Individuals who are unable to “pass” or provide gender matching I.D. information are often at risk of being turned away from job opportunities. Many trans* people are forced into “underground economies” in order to support themselves and survive. According to the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, 16% of transgender and gender non-conforming respondents said they have engaged in sex work, drug sales, or other activities for income. (p. 5) These unofficial job markets can result in trans* workers increased interaction with law enforcement and harassment and abuse, making other jobs even more unattainable. Trans* individuals without employment will not be directly affected by improved employment legislation for trans* folk. However, the increased justice and visibility for trans* people within the workplace is a win for all. With more inclusive legislation, hopefully the path to more trans* work will begin to wear down and become more accessible for those from all backgrounds to have safe job opportunities.

for trans* folk. However, the increased justice and visibility for trans* people within the workplace is a win for all. With more inclusive legislation, hopefully the path to more trans* work will begin to wear down and become more accessible for those from all backgrounds to have safe job opportunities.

Because trans* people are experiencing difficulties because of their identity, they need multiple and different approaches to tackle the root of the problem. Major problems for trans* people lie within the work sector. Between 13-47% of trans* workers report being unfairly denied a job and trans* people of color report the highest rates of these injustices. (p. 4) A general solution will not effectively combat these particular issues. The prevalence of trans* poverty shows that an effective way to protect trans* people from poverty has not been implemented, and the frequency of workplace discrimination shows that no effective solution has yet come to light. The question of how to resolve the systematic discrimination against trans* people brings us to the primary method of protection in our legal system: Anti-Discrimination Law.

A step back?

On October 4th, 2017, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that federal civil rights law did not protect transgender people in the workplace. His announcement reversed the Obama Justice Department’s declaration that gender identity was protected under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, along with race, sex, and religion. Gender identity has consistently been protected in rulings in federal appeals courts, and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has maintained that gender identity is protected by Title VII under “sex” discrimination.

transequality.org

Pro-LGBT activists and organizations, including the American Civil Liberties Union, spoke out against the Justice Department’s reversal. Greg Nevins, a workplace fairness program strategist at Lambda Legal, an LGBT+ advocacy group, called the decision “symbolic,” saying “when the federal government takes a position against your community, it’s bound to make things more difficult.” Clearly, the formal protection of trans* people under the law was seen as a major victory for many LGBT+ activists, and to have it taken away so soon was disappointing, to say the least. For the Justice Department to say that your identity is not valid enough, or worse, that is does not deserve to be protected by the law, is demora

Source: Trans Employment Program’s #TransatWork campaign

lizing and disheartening. Aside from the distress caused and the blatant disregard for human rights, what will the effects of the loss of ADL protections for trans* people be?

Failures of Anti-Discrimination Law

As horrifying as the rollback of legal protections for trans* people appears, Nevins’ stance on the decision being symbolic is important to note. Symbolically, legal protections for trans* workers provide recognition for trans* people that they are seen and that discrimination against them is wrong. Anti-discrimination law is the most dominant form of discussing trans* equality and trans* rights in the public discourse.

The main resources for trans* people who have been discriminated against are advocates of ADL, which offer sources such as these:

https://transequality.org/know-your-rights/employment-federal

https://www.lambdalegal.org/issues/transgender-rights

These resources are focused on providing legal protection for trans* people, but are they actually helpful for the majority of trans* people facing discrimination?

In practice, ADLs often fall short of actually helping the majority of trans* people. In an article in the University of Pennsylvania Journal of Law and Social Change, Ido Katri argues that the format of anti-discrimination law makes it so that people who face discrimination for only a single part of their identity are the only ones who are actually protected by anti-discrimination laws, or ADL. According to Katri, “this is because that system of legal categories included in ADL is focused on the individual who was harmed and who must belong to a protected category, and the perpetrator who must identify that category.”1 The use of protected classes in ADL expects that claimants will have coherent, compartmentalized identities that neatly fit into a class, and that discrimination will be based on this single factor, which is not reflected in reality. While anti-discrimination laws effectively protect people who are relatively privileged, like cisgender white women or white transgender men, most people are marginalized by more than one aspect of their identity. ADL fails to protect intersectionally marginalized identities, which means most trans* people in workplaces remain unprotected.

Beyond the scope of the workplace, many trans* people, as noted above, struggle to even find jobs, let alone white-collar jobs where it is easier to report discrimination complaints. Impoverished trans* people don’t necessarily need laws that protect them in workplaces they can’t even access. They do not have the resources or time for taking cases to the Supreme Court when they can barely live day-to-day. They need a large-scale intervention focused on the mitigation of poverty.

What more can we do to help trans* people?

Trans* people are disproportionately impoverished and subject to violence, but most of the efforts of government officials have been related to expanding anti-discrimination law, which is largely symbolic and excludes intersectionally marginalized identities. Judging from the reactions to Sessions’ announcement, legal protections for trans* people are very important to many people, despite their relative ineffectiveness. After all, it is important that the government recognize that your identity should not be discriminated against in the workplace, even if the impact is only symbolic. However, if discrimination against trans* people is to improve, anti-discrimination law needs to be implemented from an intersectional point of view.

Why is an intersectional approach important for legislation?

In their piece on “International Human Rights and Intersectional Discrimination,” Truscan and Bourke-Martignoni critique the “‘single-axis’ approach to enforce legal provisions prohibiting discrimination”2 that the international human rights community has been taking. They argue that an intersectional approach is an essential framework to consider when combatting discrimination through anti-discrimination laws and policies. This approach would be a groundbreaking strategy for trans* activism to adopt when looking to tackle trans* issues. So why would this framework be so vital? In court, complaints can only be filed under one aspect of discrimination (i.e. if you believe you have been discriminated against for being a black trans* woman, you can only go to court for being discriminated against because you are black, or trans, or a woman, but not all of them). The single-axis framework fails so many people who are potential victims of discrimination in the workplace because most people are not marginalized by only one segment of their identity.

Source: Redbubble

As for addressing trans* poverty, employment anti-discrimination law doesn’t do much. For individuals who are targeted for discrimination, the system explained above does very little to protect them if they are marginalized intersectionally. The solution to disproportionate poverty and discrimination doesn’t need to be entirely trans*-oriented to be effective. Targeting poverty in general will help trans* communities, as poverty seems to be the greatest barrier to survival and success. Seeing as trans* people are disproportionately unemployed, which forces them into underground economies and puts them in conflict with law enforcement, a solution targeting poverty among all people would help trans* people more than symbolic laws that can only affect them if they can get a white-collar job. A reasonable step here that legislators could take is the expansion of social programs such as financial assistance for unemployed people and Medicaid, improving public housing, intervention in cases of homelessness, improving law enforcement to decrease instances of police violence, and helping those who engage in underground economies stay safe through the decriminalization of sex work and better access to drug addiction treatment. Resolving discrimination against trans* people requires a critical view of current systems, which consistently fail the people who need the most help. While destroying and rebuilding entire systems may not be necessary to mitigate disproportionate poverty among trans* people, it is certainly important to examine the systems we currently use to protect vulnerable people, and how we might do better by them.

Evelyn Gibson, Olivia Alderman

Endnotes

1Katri, Ido. “Transgender Intrasectionality: Rethinking Anti-Discrimination Law and Litigation.” University of Pennsylvania Journal of Law and Social Change, vol. 20, no. 1, 2017, p. 67.

2Truscan, Ivona, and Joanna Burke-Martignoni. “International Human Rights Law and Intersectional Discrimination.” The Equal Rights Review, vol. 16, 2016, p. 103.

Speak Your Mind